- Julija Sukys

- "Let us now praise famous men": On Breaking Conventions and Women's Biography

This morning I read a really interesting conversation with Michael Scammel, the biographer of Alexsandr Solzhenitsyn and Arthur Koestler. A lot of what Scammel said about his path to biography resonated with me. He describes having wanted to become a fiction writer in his twenties (just as I did), only to find that he “didn’t have the stamina for it.” The urge to be a biographer crept up on him without his realizing it. And the questions of biography — of how tell a life in an engaging and instructive way — came to him naturally (just as they have to me).

Scammel talks about what a biographer must do: wear learning lightly, entertain as well as instruct, write what is genuinely fact-based, and hone the novelistic skills of setting a scene.

What a biographer must never, ever do, Scammell underlines, is lie. “The oath is against invention,” he stresses, “if you’re not sure of something, you don’t put it in.” The one way around uncertainty is to speculate, but honestly. “You have to confess and say, ‘This is what I think may have occurred, but I can’t prove it.’ And that way you have your cake and eat it too.”

All in all, it’s a great conversation. Reading Scammell’s descriptions of his process, I recognized many of my own struggles writing Epistolophilia, but, I must admit, that something was nagging at me as I read this interview — I couldn’t help wondering: well, what about women?

In the whole conversation, only one female biographer, Janet Malcolm (author of many books, including Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice) is mentioned. And, interestingly, she’s held up as an exception in her approach to biographical writing, since her books “aren’t biographies in the usual sense.”

This is no coincidence. It seems to me that there’s a gender divide in biography.

Women writing about women almost always produce texts that aren’t “biographies in the usual sense.” This is because women’s lives (and here I’m thinking both of female biographical subjects as well as female biographers) are structured differently and have different rhythms and arcs than male lives (or, I suppose, “usual lives”). It’s something I grappled with in a chapter called “Writing a Woman’s Life” in Epistolophilia. Here’s an excerpt:

Why have women traditionally written so little when compared with men? And what needs to change in women’s lives in order to make writing possible? Why have women been so absent from literary history? The answer, Virginia Woolf tells us in A Room of One’s Own, lies in the conditions of women’s lives. Women raise children, have not inherited wealth, and have had had fewer opportunities to make the money that would buy time for writing. Women rarely have partners who cook and clean and carry (or share equally) the burden of home life. Our lives have traditionally been and largely continue to be fractured, shared between child care, kitchen duties, family obligations. To write, what a woman needs most is private space (a room of one’s own), money and connected time (that only money can buy). Woolf wrote her thoughts on women and writing in the 1920s, a time before all the ostensibly labor-saving devices like washing machines, slow cookers, microwave ovens, dishwashers and so on. Most North American women now work outside the home, and most can probably find a corner in their houses to call their own. Problem solved? No. Despite all this, we still find ourselves fractured and split.

Women biographers often enter into the text to dialogue with their subjects, instead of vanishing in the shadow of her creative achievement (which, Scammell’s interviewer Michael McDonald reminds us, used to be the mark of a good biographer). Increasingly, we do not take up Ecclesiasticus’s call, "Let us now praise famous men." Instead, more and more of us answer the faint call of foremothers to excavate their invisible and unknown lives out of the detritus of the past.

When Scammell explains his reasons for abandoning an initial attempt to insert himself into Koestler’s story, choosing instead to write the biography in the “usual third-person style,” I respect his reasoning. First-person narrative, in his context, may indeed have been distracting and mightn’t have added much value to the text.

In a weird way, I sympathize accutely, because I desperately wanted to write a “straight biography” of my subject, Ona Šimaitė in the “usual third-person style.” It didn’t work.

“The conventions are there for a reason,” says Scammell. Perhaps.

And they work very well for certain tasks, like praising famous men. They don’t, however, work so well for telling the lives of obscure women.

I learned this the hard way.

After reading this interview, I’m left with many questions. Here I am on the eve of publishing a biography of a woman, and I wonder about the gendered aspect of the genre that has chosen me. Will women biographers, feminist biographers, and archaeologists of the feminine past forever be considered exceptions, curiosities, and breakers of convention? How wide must the margins grow before they finally touch the centre? Will women’s biography ever become simply biography “in the usual sense”? And if it did, what would we think?

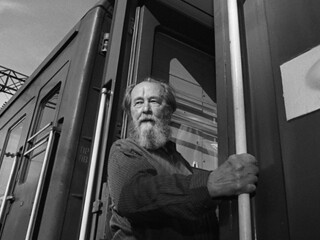

[Photo: Alexander Solzhenitsyn, by openDemocracy]

[This post was originally published at http://julijasukys.com]

Writing Status Badges

Writing Status Badges

Featured Members (7)

Writing Status Badges

Thanks, Meg. I too am frustrated, but still somehow hopeful. I love the discussion that this post sparked about gender biases across all levels of our industry.

The thing that is mentioned again and again is what a powerful market women are. SheWrites proves that over and over again. Not only do women form communities upon communities of writers, but also of readers. Can we not set our own terms, define or refuse to set our own conventions, and be our own market?

Really interesting, Julia. The gender divide in all areas of literature continues to amaze me. And frustrate me.

This is so fascinating. My daughter is 6, and I took her to see the violinist Joshua Bell this past weekend. I was sitting there thinking - there are so many more women than men who study violin, and yet almost all the "grand soloists" are men. Why should this be?

Why should this be?

Really interesting post Julija. Unfortunately the world of literature and publishing is no different to the unequal treatment of women when it comes to women's words or women's lives. While it has improved in great strides, we can still see instances where inequality exists, just as you highlight in the genre of biography.

Writing about women's history is no different. It used to be that most of the books about historical events or influential people in a town or in a particular period were mostly men. Women, for the most part, were absent and therefore, not given due credibility for their lives and contributions. Since this has been acknowledged and more women's history has been written, the courage, tenacity and bravery they have shown or the contribution they did actually make has, in some instances, redefined events, or made people think 'wow'.

But I wonder if women's biography is treated differently because it is the nuts and bolts of a woman's life. It is the actual lived reality and not the idealised versions of what it means to be a woman, and the many roles we take on in our lives. I think publishers also play a role in this (although this is slightly changing with the rise in self-publishing, online and otherwise), in that when something is published it is given a certain credibility. This has meant that the biographers who are men and the men who are the 'subjects' are given more credibility and reliability as authors, and as providing confirmation of the subject's life. The lack of women biographers, and lack of women as 'subjects' of biographies doesn't provide women the same credibility or reliability as authors nor women the same confirmation of their lives.

My last point is that your right to question the role which conventions play. I agree that there is a 'but' in there. Conventions are there for a reason, but at the same time conventions act as a tool in which to limit an individuals access to something or if the conventions are not met, are used as a tool of rejection. This has huge ramifications if the playing field is already unequal.

Just finished Composing a Life by Mary Catherine Bateson and she argues the same thing about fractured lives of women, although she describes it differently. The best outcome of this stop-and-go life of women is at a certain age seeing how the threads weave together to form a whole.